A few weeks ago at church, the minister talked about something called the “Dunning-Kruger Effect.”

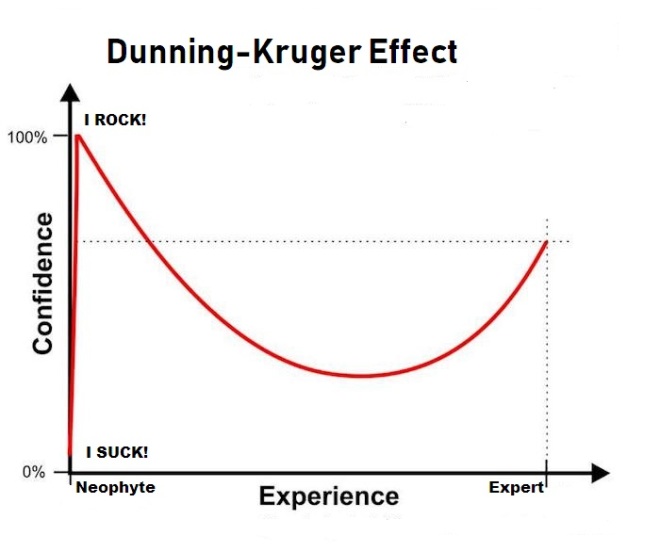

This concept, defined by psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger, describes the cognitive bias of inexperience that causes people who know almost nothing about a topic think they are experts because they don’t know enough to realize the extent of their ignorance.

If you’ve ever critiqued a manuscript for a beginning writer, you know exactly what this is. The newbie will bring you her precious creation and hand it over, dewy-eyed with confidence that the next day (because it’s so good you’ll stay up all night reading it), you’ll call to tell her that she is the next J.K. Rowling/Nora Roberts/E.L. James/Gillian Flynn.

A couple of days later, you crack open the manuscript and it’s terrible. The characters are inconsistent, the point-of-view hops from head to head, the dialogue sounds like kindergartners (or rocket scientists) chatting over Play-Doh, and the plot is nowhere to be found.

It is, in fact, a very typical first attempt at writing a novel. It’s where most (though not all) of us start our writing careers.

So now you have the painful task of giving Ms. Newbie that little shove off the “I ROCK” platform and down the precipitous slope of reality to a more realistic view of what she still has to learn.

It is a slide every novice has to take if she wants to get better, but there’s a good portion of would-be writers whose egos aren’t tough enough to survive that free-fall. And no one wants to be the meanie who turned a budding Ernestina Hemingway into an embittered lush who drinks because a hater destroyed her dreams.

So how do you help a new writer make that first step down without bottoming out?

To be honest, my usual approach is to decline giving feedback to beginners. I’m pretty tough even on experienced writers, which means I’m not the ideal mentor for the green-as-grass newbie.

On the occasions when I can’t avoid the task, I look for things the author is doing well–an interesting character, a catchy turn-of-phrase, an intriguing premise. And I try to ask questions to help the writer see where she’s maybe not coming across as clearly as she thinks. And I try to remember that no one learns to write in a day, or even in a single book, so there’s no need to point out every problem I see.

How do you handle working with newbies?

I’m a retired editor, primarily of nonfiction material. I did some editing for first-time novelists for pay when I was still working, and part of my job was to give detailed critiques/explanations of why I suggested what I did. And then I stopped working for novelists because I couldn’t charge them enough for the time I was putting in, I didn’t want to shortchange them by not pointing out everything I saw, and I didn’t want to go broke editing first-time writers. Now that I’m retired, I don’t critique manuscripts for anyone except the Ladies, if asked, and my two critique partners, both of them are very experienced and accomplished writers. I don’t even offer to judge contests anymore. I can’t afford to give away my time like that. Kudos to you for making the effort!

It’s time-consuming, that’s for sure. If you find someone who’s really committed to improving and can take your feedback and really make big strides, though, it’s worth it.

I recently critiqued (for free) a manuscript by a published writer. It was a rough read, not that her writing was terrible (it wasn’t really great, either), but it was a historical and she didn’t know her history. I pointed out a few obvious, glaring flaws, giving detailed explanations as to why they wouldn’t hold water for any reader who had a modicum of knowledge of the time, then reduced my comments to “check your history” for everything else that seemed implausible.

Because 2018 was the year of NO and 2019 is the year of DEADLINES (which I still have to sit down and set), I’ve decided that NO still carries over for 2019 and I won’t be critiquing anything for anyone whose writing I’m not familiar with, which basically limits me to the Eight Ladies and my two CPs. Until I get paid to teach a class, that is. 😉

I’m committed to judging some contests this year, and I owe some payback to folks who’ve read for me over the years, but otherwise I’m going to emulate your 2019 word and say “No.”

Like you, Jeanne, I’m committed to some judging this year. And I would read for any of the Ladies anytime, knowing they would take my critique as it would be offered: as a genuine attempt to help make an awesome story even better (because this group tends to write awesome stories). The only other critique partnership I might consider is one that gets set up through WFWA, with one or two other writers who are far enough along in their careers that they really want to hear the good, the bad, and the ugly.

Other than that, I’m out of the critique game. I lost a friendship over it last year, I think because she didn’t *really* want a critique, but more of an ‘atta girl’, which is just not in my nature. (That’s my take. Hers might be that I’m a terrible critique partner and an overall horrible person. I don’t know, because she’s ghosted me.) At any rate, it was a total bummer.

To continue a metaphor, your experience with your lost friendship is an example of what happens when you try to nudge someone off the “I rock” platform and they’re not ready to make that leap. And if someone can’t make that leap, they’re definitely not ready for the wild and woolly world of Amazon and Goodreads reviews.

Pingback: Nancy: The Fine Art of Receiving a Critique – Eight Ladies Writing

I try to remember to use the positive-negative-positive sandwich. By bookending with the things done well, you A) open the recipient to be more capable of receiving the crit, and B) ending on a hopeful note they can go back to. For whatever seems to be the biggest issue for the new writer, e.g., dialogue, I’ll recommend a book I found help. If global issues, I’ll recommend one of the three books that tackle global perspectives. That was what a writer did for me, and I’m forever grateful for the first one on the list; and then the group told me a second book, and I loved it, too. The third I found when a NYT best seller shared that he always uses a workbook technique.

I also try to remember to extract out the word “you,” leaving the focus on the work itself, rather than the person who created it. It’s a fine line, but it’s a technique, again, to try to enable a recipient to back away from the I’m-being-attacked response.

Depending on how the first few crits go, I may decline to critique their pieces in the future. Like you, I’ve reminded myself I am allowed to say “no.” My investment in critiquing is lost writing time. If the recipient isn’t ready to hear it, I remind myself it’s on them, not me.

Good approach! I especially like the idea of recommending books that address the particular issue. Like you, that’s the thing I’ve found most helpful.

Super-late to the party, but I think it’s important to ask your critique receiver exactly what they want. Do they want an “atta girl!”? Do they want raw data about reactions? (And I think you better explain that in-the-moment reactions are just that; they should use other beta readers to triangulate to see if there’s a problem, or if it’s an idiosyncratic reaction.) Make sure they know Neil Gaiman’s rules of writing — especially the one that goes something like, readers may not be able to explain clearly what’s wrong, so take explanations with a grain of salt. However, they do know something’s wrong, so pay attention to that.

Most contests have a form, which can be helpful. In addition, I think all the Ladies who have entered contests have received some WTF advice from people. And all of you have survived! So there’s that.

Can’t fix another person’s writing — only they can do it. We can only hope to shed a little illumination about how our brains work and hope that we are “typical” readers, I guess.

Good points, Michaeline. Not everyone is ready for the Jenny Crusie boot camp!